Surgery for pituitary gland tumours

Surgery is usually used to treat pituitary gland tumours. The type of surgery you have depends mainly on the size and type of the tumour and if the tumour has grown into (invaded) nearby areas. When planning surgery, your healthcare team will also consider other factors, such as your age and overall health.

Surgery may be done for different reasons. You may have surgery to:

- completely remove the tumour

- remove as much of the tumour as possible before other treatments

- relieve pressure from the tumour on nearby areas

- lower hormone levels and ease symptoms caused by a tumour that makes too many hormones (a functioning tumour)

The following types of surgery are used to treat pituitary gland tumours. You may also have other treatments before or after surgery.

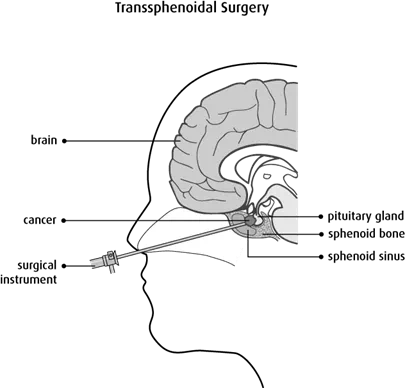

Transsphenoidal surgery

Transsphenoidal surgery is the most common type of surgery used to treat pituitary gland tumours. It is done under general anesthetic (you will be asleep). The surgeon uses surgical tools to get to the tumour through the nose and the sphenoid sinus (transsphenoidal). This surgery may be used to remove some or all of a pituitary gland tumour.

For conventional transsphenoidal surgery, the surgeon makes a small cut (incision) along the wall of cartilage and bone that separates the 2 nostrils (or behind the upper lip above the teeth, but this is rare). Using surgical tools (called curettes), the surgeon goes through the sphenoid bone and sphenoid sinus to reach the pituitary gland and remove the tumour. The incision is then closed and the nostrils are packed with gauze or another type of material. Most people stay in the hospital for a few days after the surgery.

Endoscopic transsphenoidal surgery is a newer way to do transsphenoidal surgery. It uses an endoscope to get to the pituitary gland and remove the tumour. An endoscope is a thin tube-like instrument with a tiny camera lens and light on the end.

Endoscopic transsphenoidal surgery may be done to remove small tumours if they are in a suitable position. Sometimes endoscopic transsphenoidal surgery can’t be done or can’t completely remove the tumour because of the position of the tumour and the shape of the sphenoid sinus.

The surgeon makes a small cut inside the nose at the back. The endoscope is passed through the nose and then through the sphenoid bone and sphenoid sinus to reach the pituitary gland. Small tools are passed through the endoscope to remove the tumour.

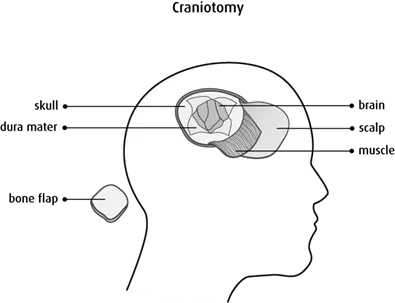

Craniotomy

A craniotomy is surgery that opens the skull to remove a tumour. It is used to remove very large pituitary gland tumours that can’t be removed with transsphenoidal surgery.

A craniotomy is done under general anesthetic. During the surgery, the surgeon makes a cut in the scalp. A piece of the skull is removed to expose the area where the pituitary gland tumour is growing. This piece of skull is often called the bone flap. The surgeon then makes a cut in the covering of the brain (dura mater) and pulls it apart slightly to find and reach the tumour. The surgeon removes as much of the pituitary gland tumour as possible.

After the tumour is removed, the dura mater is tightly stitched together, the piece of skull is replaced with small screws and plates, and the scalp is closed with stitches or staples. If the brain is very swollen after surgery, the piece of skull may be replaced later when the swelling has gone down. Healing usually takes several weeks.

Bilateral adrenalectomy

A bilateral adrenalectomy is surgery to remove both

A bilateral adrenalectomy may be done through a cut in the abdomen or lower back above the hip (called an open bilateral adrenalectomy). The surgeon may use

Side effects

Side effects can happen with any type of treatment for pituitary gland tumours, but everyone’s experience is different. Some people have many side effects. Other people have only a few side effects.

If you develop side effects, they can happen any time during, immediately after or a few days or weeks after surgery. Sometimes late side effects develop months or years after surgery. Most side effects will go away on their own or can be treated, but some may last a long time or become permanent.

Side effects of surgery will depend mainly on the type of surgery and your overall health.

Transsphenoidal surgery may cause these side effects:

- sinus headache and congestion

- diabetes insipidus, which causes extreme thirst and the need to urinate often

- infection and inflammation of the

meninges (meningitis) - a

cerebrospinal fluid leak from the nose

A craniotomy has a higher chance of damaging large blood vessels, brain tissue or nerves. It may cause these side effects:

- neurological problems, such as weakness, numbness, vision problems and seizures

- diabetes insipidus, which causes extreme thirst and the need to urinate often

- not enough pituitary hormones being made (hypopituitarism)

- a

hematoma - a

cerebrospinal fluid leak from the wound - infection

A bilateral adrenalectomy may cause:

- pain

- less urine production

- changes in blood pressure

- low blood sugar (glucose)

Tell your healthcare team if you have these side effects or others you think might be from surgery. The sooner you tell them of any problems, the sooner they can suggest ways to help you deal with them.

Questions to ask about surgery

Find out more about surgery and side effects of surgery. To make the decisions that are right for you, ask your healthcare team questions about surgery.