Urinary diversion

A urinary diversion is surgery that makes a new way for urine (pee) to leave the body. Urine is your body’s liquid waste. A urinary diversion is done when the normal flow of urine is blocked or the bladder can’t store urine. The most common reason to have a urinary diversion is after the whole bladder is removed for bladder cancer.

A urinary diversion may also be called a urinary tract diversion or bladder diversion.

Why a urinary diversion is done

Urine is made by the kidneys and then travels along 2 long tubes called ureters to the bladder. The urine is pushed out of the bladder through the urethra where it leaves the body. A urinary diversion is done when the urine can’t flow out of the body as usual.

A urinary diversion can be done:

- for bladder cancer when the whole bladder is removed (called a radical cystectomy)

- after pelvic exenteration surgery for some advanced cancers

- to go around a blockage (obstruction) and relieve blocked urine flow

- when there is damage to the bladder from radiation therapy or other cancer treatments

- for non-cancerous (benign) reasons such as urinary tract stones, an enlarged prostate, birth defects, nerve problems and tumours

Types of urinary diversions

There are different types of urinary diversions. The type of urinary diversion you have depends on many factors, including:

- your age

- how well you can move around

- how well the intestine, liver and kidneys are working

- other medical problems you have

- if you have had radiation therapy

- how close the cancer was to the urethra

- how long you are expected to live (life expectancy)

A urinary diversion can be permanent or temporary depending on why it is done. A permanent urinary diversion can be either incontinent or continent.

Incontinent urinary diversions

With an incontinent urinary diversion, you don’t control urination. A

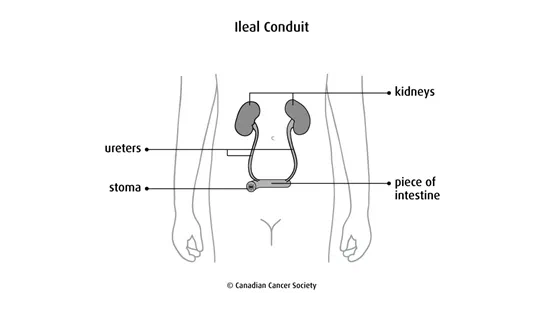

An ileal conduit (also called a loop diversion) is the most common type of urinary diversion done. The surgeon removes a piece of the small intestine (

A cutaneous ureterostomy is when the surgeon attaches one or both of the ureters directly to the wall of the abdomen. The urine drains out of 1 or 2 stomas. This surgery is not done very often because of the increased risk of serious problems, such as kidney failure.

Continent urinary diversions

With a continent urinary diversion, you control urination. The surgeon makes a pouch to hold the urine. You drain the urine from this new pouch either with a tube (

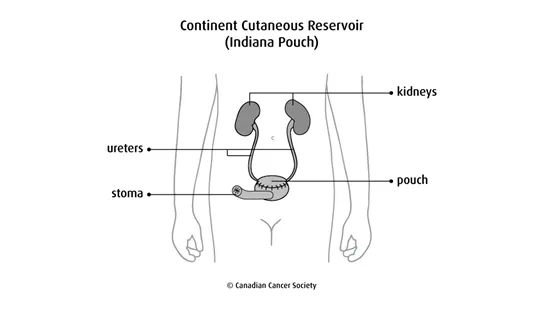

A continent cutaneous reservoir (Indiana pouch) is also called a continent diversion with catheterizable cutaneous stoma. The surgeon creates a pouch using the right side of the colon (cecum and ascending colon) and a piece of the small intestine (end of the ileum). There are different types of pouches, but the Indiana pouch is the most common. The pouch is attached to an opening (stoma) made in the wall of the abdomen and skin. You drain urine from the pouch by inserting a tube into the opening every 4to6 hours.

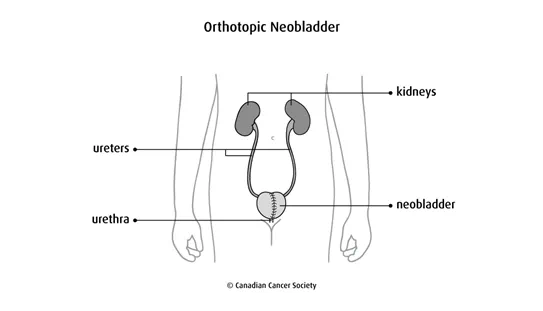

An orthotopic neobladder is when the surgeon makes a pouch (called a neobladder, or new bladder) usually from part of the small intestine. (Part of the colon may be used in some cases.) The ureters are attached to the pouch, which is then attached to the urethra. You empty the pouch by urinating normally. An orthotopic neobladder is a more difficult type of surgery than other urinary diversions and there is more chance of problems (complications). So it is usually done in younger people without serious medical problems.

Ureterosigmoidostomy is surgery where the ureters are connected to the sigmoid colon (the last part of the large intestine). The urine leaves the body with the stool (poop) through the anus. This surgery is not done very often because of the increased risk of many problems, including kidney infections and colon cancer.

Temporary urinary diversions

Sometimes a urinary diversion is temporary. It can be kept in place for a few days or several weeks.

A urinary catheterization is a common type of temporary urinary diversion. A thin, flexible tube called a catheter is put into the bladder to drain urine into a bag outside the body. The tube is inserted into the bladder through the urethra or a small cut (incision) just under the belly button. A urinary catheterization is often used after surgery in the lower abdomen to allow the area to heal.

A nephrostomy uses a small tube inserted directly into a kidney through the skin. The urine travels through the tube into a bag outside the body. A nephrostomy may be used while a kidney stone is removed. It may also be done when the ureters are inflamed or blocked and urine isn’t flowing properly.

How a urinary diversion is done

Your surgeon will usually mark the abdomen where the stoma will be to make sure it is in a convenient and comfortable place. Your surgeon or healthcare team may also discuss the type of pouch that you will need to use after the surgery. You may be given antibiotics before surgery to help prevent infection.

A urinary diversion is done in a hospital using a general

During surgery, it is common to do a radical cystectomy first to remove the whole bladder. But it depends on the reason for doing the urinary diversion. A urinary diversion may be done without removing the bladder.

The surgeon uses part of your intestine to make a urostomy or internal pouch. The ureters are joined to the reconstructed intestine (conduit or reservoir) by a procedure called anastomosis. One end of intestine may be brought to an opening on the surface of the abdomen and the surgeon stitches the edges to the skin of the abdomen to make the stoma. The surgeon closes the large cut in your abdomen with stitches or staples.

After surgery, you will need to stay in the hospital for several days. You will be given pain medicines to keep you comfortable. Fluids and solid foods will be introduced slowly.

Problems after surgery

Problems (complications) can happen after urinary diversion surgery. They can happen early on after surgery (immediately after or within a few days or weeks). Sometimes late problems develop months or years after surgery. Some problems are only temporary and can be treated, but some may last a long time or become permanent.

Any problems you have depend mainly on the type of urinary diversion done and your overall health.

A urinary diversion may cause these problems:

- infection, which may cause fever or cloudy or strong-smelling urine

- a paralyzed or less active intestine (paralytic ileus)

- a blocked intestine (bowel obstruction)

- urine leaking into the abdomen

- scarring around the ureters

- narrowing of the ureters (stricture)

- stool leaking from the intestine into the abdomen

- collection of fluid in certain areas such as developing a

seroma orhematoma - urinary tract stones (urolithiasis or urinary calculi)

- back-up (reflux) of urine into the kidneys

- kidney failure

- inflammation of the internal pouch or reservoir (pouchitis)

- problems with the stoma such as bulging around the stoma (parastomal hernia) or a narrowing of the stoma (stomal stenosis)

- break of the neobladder (called a rupture)

Living with a urinary diversion

While you are in the hospital a WOC (wound, ostomy and continence) nurse will teach you how to live with the urinary diversion and care for a urostomy.

Your healthcare team or WOC nurse could talk with you about:

- eating, drinking and nutrition

- physical activity

- showering and bathing

- relationships

- how to clean and care for a stoma

- how to empty an internal pouch (continent cutaneous reservoir)

- what to do if you have problems

- when to visit the surgeon for follow-up

- support groups in your area

Caring for an ostomy

Specially trained nurses will teach you and your family how to care for and live with your ostomy. These nurses are called wound, ostomy and continence (WOC) nurses. They may be part of an association called Nurses Specialized in Wound Ostomy and Continence Canada (NSWOCC).

Pouch systems

If you have a colostomy, ileostomy or urostomy, a pouching system is used to collect stool or urine from the stoma. The system may have 1 or 2 pieces. They can also be closed-end or drainable.

Pouches are odour-proof even if they are full of urine or stool. There are many different pouch options to try. The pouch can’t be seen under your clothing.

A WOC nurse will help you find the system that suits your needs. They will teach you how and when to empty or change the pouch, depending on the type of stoma you have and your stool or urine output. On average, drainable pouching systems are changed twice a week. Closed-end systems are usually changed daily. It is important to change pouching systems before they leak. Don’t use tape to patch a leak because it can lead to skin problems around the stoma.

Stoma care

Your WOC nurse will teach you about cleaning the stoma and the skin around the stoma. Use only warm water and a soft cloth to clean the skin and stoma. Don’t use soap, alcohol or baby wipes because they can irritate the skin.

Showering or bathing

Your WOC nurse will teach you about showering and bathing with a stoma.

If you have a colostomy, ileostomy or urostomy, you can shower or take a bath with the pouching system on or off. The water from the bath or shower will not loosen the pouching system. The pouching system will not fall off if it gets wet. You don’t need to cover the pouching system in plastic to protect it from the water. If you have a tracheostomy, you can bathe or shower as long as the stoma is covered.

Adjusting to daily life

Talk to your WOC nurse or healthcare team about questions and concerns you have about returning to your daily life after ostomy surgery. They can help you adjust and manage your stoma during your usual activities.

Clothing

Pouching systems are designed to lie flat against your body, so you should be able to wear the same clothing you did before surgery. You can also choose to buy clothes that are specially designed for an ostomy, including underwear and swimsuits.

Physical activity

An ostomy doesn’t get in the way of most physical activities. Don’t do heavy lifting for 3 months after your surgery to allow your abdominal muscles and incision (surgical cut) to heal. A physiotherapist can help you safely strengthen your abdominal muscles. They can also help you return to your usual activities over time.

Work

You can go back to work once you recover from ostomy surgery. Some people with an ostomy may not be able to do jobs that require heavy lifting. Talk to your WOC nurse or healthcare team if you have questions or concerns about returning to work after surgery.

Travel

You can travel as you usually would after you have ostomy surgery. Travelling by airplane doesn’t affect the pouch because the cabins are pressurized. It is a good idea to travel with about twice as many supplies as you would normally use at home. Carry the supplies with you – don’t check them in with your luggage. You may also want to know where to contact a local WOC nurse during your travels.

Sex and intimacy

You can have strong, supportive relationships and a satisfying sex life after ostomy surgery. Talk to your WOC nurse, a counsellor or other people who have an ostomy if you or your partner have questions or concerns about sex and intimacy.

To find out more about intimacy after ostomy surgery, see the information published by the Ostomy Canada Society.

Emotional and mental adjustment

People who have ostomy surgery cope with both physical and psychological changes. They need to adjust to changes in their bladder and bowel function.

You may have a pouch to collect urine or stool on your abdomen. Body functions are usually private topics, so you might not feel comfortable talking about them openly. This can make you feel like you are the only one with an ostomy. But many people in Canada are living with an ostomy. Doctors, hairdressers, teachers, police officers and other people in your community may have an ostomy and you would not know.

Talk to your WOC nurse to find out more about resources in your community that can help you adjust to the emotional and mental changes that come with an ostomy. They can also tell you about support groups with trained volunteers who have been through what you are going through.

Special considerations for children

Preparing children before a test or procedure can help lower their anxiety, increase their cooperation and develop their coping skills. This includes explaining to children what will happen during the test, such as what they will see, feel and hear.

Preparing a child for a urinary diversion depends on the age and experience of the child. Find out more about helping your child cope with tests and treatments.