Surgery for prostate cancer

Surgery is usually used to treat cancer that hasn't spread outside of the prostate. The type of surgery you have depends mainly on the stage of the cancer. When planning surgery, your healthcare team will also consider other factors, such as your age, overall health and life expectancy.

Surgery may be done for different reasons. You may have surgery to:

- completely remove the tumour

- remove as much of the tumour as possible (called debulking) before other treatments

- reduce pain or ease symptoms (called palliative surgery)

- treat cancer that comes back (recurs) after other treatments (called salvage surgery)

The following types of surgery are commonly used to treat prostate cancer. You may also have other treatments before or after surgery.

Radical prostatectomy

A radical prostatectomy removes the prostate and some tissues around it, including the seminal vesicles. The surgeon may also remove lymph nodes from the pelvis (called a pelvic lymph node dissection) at the same time as a radical prostatectomy.

A radical prostatectomy is the most common surgery used to treat prostate cancer in healthy men. It is used when the cancer hasn't spread outside of the prostate. It may also be used to treat men whose prostate-specific antigen (PSA) level starts to rise after treatment with radiation therapy or cryosurgery (called a biochemical recurrence or biochemical failure). When this surgery is used to treat a recurrence, it is called salvage surgery or a salvage radical prostatectomy.

Approaches to radical prostatectomy

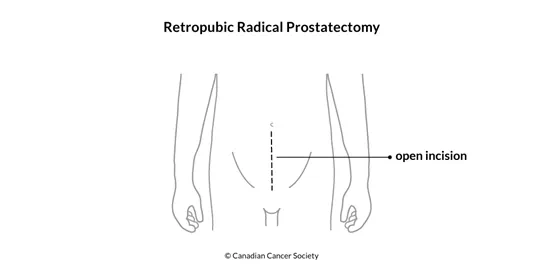

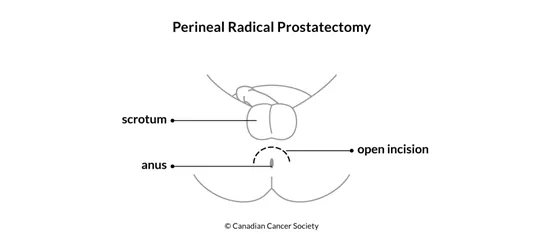

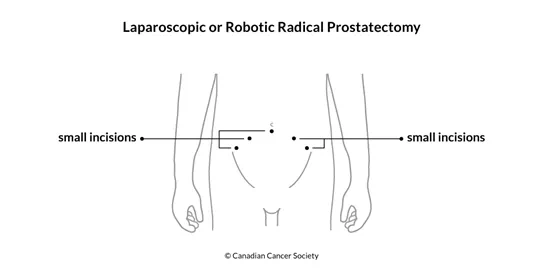

Surgeons can use different approaches and techniques to remove the prostate. They can make a large incision (cut) to reach the prostate (called an open radical prostatectomy). They can also use laparoscopic or robotic techniques, which are done through smaller incisions in the pelvis. Laparoscopic and robotic types of surgery are less invasive than an open radical prostatectomy. Men often have shorter recovery times, less blood loss, less pain and shorter hospital stays with these procedures.

Retropubic radical prostatectomy is done through an incision in the lower abdomen. The surgeon can also remove lymph nodes from the pelvis through the same incision. In Canada, a retropubic radical prostatectomy is the most common approach to removing the prostate to treat cancer.

Perineal radical prostatectomy is done through an incision in the area between the scrotum and the anus (called the perineum). This surgery usually doesn't take as long to do as a retropubic radical prostatectomy, but it may lead to more problems with getting an erection (called erectile dysfunction). In addition, surgeons can't remove pelvic lymph nodes through the same incision so they would have to do a separate procedure through a small cut in the lower abdomen to remove them.

Laparoscopic radical prostatectomy uses a laparoscope (a tube-like instrument with a light and tiny video camera) and other surgical instruments passed through small cuts. A laparoscopic prostatectomy has some advantages over an open radical prostatectomy, including less blood loss and pain, shorter hospital stays, faster recovery and less time with a catheter.

Robotic radical prostatectomy is a type of robotic surgery. The surgeon sits near the operating table and uses remote controls to move robotic arms. The robotic arms have tiny video cameras and surgical instruments that remove tissue through small cuts. The robotic arms can bend and turn like a human wrist. A robotic prostatectomy also has advantages over an open radical prostatectomy including less blood loss and pain, shorter hospital stays, faster recovery and less time with a catheter.

Nerve-sparing radical prostatectomy

A nerve-sparing radical prostatectomy aims to avoid damaging the nerves to the penis, which helps reduce the risk of erectile dysfunction. It may be an option with any of the approaches to radical prostatectomy, but it is more successful with early stage prostate cancer and in younger, sexually active men. Your chances to recover erection following surgery will depend on your age, your ability to get an erection before surgery and whether the nerves were cut.

It is hard for surgeons to know before surgery if the nerves can be spared. So they will decide if nerve-sparing surgery is possible when they see the prostate and tumour during surgery. Surgeons who do many radical prostatectomies tend to report lower impotence rates than doctors who do the same surgery less often. Ask your doctor about their success rates and what the outcome might be in your particular case.

Pelvic lymph node dissection (PLND)

A pelvic lymph node dissection (PLND) (also called a pelvic lymphadenectomy) removes lymph nodes from the pelvis. The surgeon can use an open or laparoscopic approach to remove the lymph nodes. A pelvic lymph node dissection may be done during the same surgery as a radical prostatectomy or it may be done as a separate procedure.

Doctors do a pelvic lymph node dissection to find out if the cancer has spread to the pelvic lymph nodes. They usually don't remove pelvic lymph nodes if there is only a low risk that the prostate cancer will come back after treatment.

Find out more about a pelvic lymph node dissection (PLND).

Cryosurgery

Cryosurgery is a procedure that destroys cancer cells by freezing them. It is also called cryoablation, cryosurgical ablation or cryotherapy. Cryosurgery may be used to treat low-risk, early stage prostate cancer. It may be used if you are unable to have surgery or radiation therapy. Cryosurgery may also be used to treat recurrent prostate cancer.

Cryosurgery delivers an extremely cold liquid or gas to the prostate through a metal tube called a cryoprobe. The doctor will often use a transrectal ultrasound to guide the cryoprobe to the tumour. The area is allowed to thaw and then is frozen again. The freeze-thaw cycle may need to be repeated a few times.

Find out more about cryosurgery.

Transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP)

Transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP) removes part of the prostate through the urethra. The surgeon passes a resectoscope through the tip of the penis and up the urethra to reach the prostate. A resectoscope is a type of endoscope that uses a magnifying instrument with a light and video camera. The surgeon passes tools through the resectoscope and uses a thin wire with an electric current or a laser to cut away and remove prostate tissue around the urethra.

TURP is most commonly used to treat benign prostatic hyperplasia, which is a non-cancerous condition of the prostate. It is sometimes used to help relieve urinary (peeing) problems caused by an enlarged prostate blocking the urethra. This is done as palliative treatment for those with advanced prostate cancer or those who are not healthy enough for a radical prostatectomy.

Side effects

Side effects can happen with any type of treatment for prostate cancer, but everyone's experience is different. Some people have many side effects. Other people have few or none at all.

If you develop side effects, they can happen any time during, immediately after or a few days or weeks after surgery. Sometimes late side effects develop months or years after surgery. Most side effects will go away on their own or can be treated, but some may last a long time or become permanent.

Side effects of surgery will depend mainly on the type and site of surgery and your overall health.

Surgery for prostate cancer may cause these side effects:

- bleeding and infection

- sexual problems (erectile dysfunction, changes in orgasm)

- fertility problems

- lymphedema

- shortening of the penis

- inguinal hernia

- loss of bladder control (called urinary incontinence)

- swelling in the genital area

- leakage of stool (poop) from the anus

- leakage of urine (pee) during ejaculation (called climacturia)

Tell your healthcare team if you have these side effects or others you think might be from surgery. The sooner you tell them of any problems, the sooner they can suggest ways to help you deal with them.

Questions to ask about surgery

Find out more about surgery and side effects of surgery. To make the decisions that are right for you, ask your healthcare team questions about surgery.